of the "1st of May" extracted from a corpus of German-language fiction. ]

Last Friday, German radio station Bayern 2 asked me for an interview about our research on the role of the month of May in literature (and about the practice of Digital Humanities in general, for that matter). The announcement is here – unfortunately, they didn’t put the interview online, but if anyone wants to listen to it, I can send them an mp3 copy.

I took this opportunity to revisit my earlier research on date extractions from literature, which I started with Jannik Strötgen right after we met at his poster at the 2013 Herrenhausen Conference “(Digital) Humanities Revisited”. Although our work was mostly finished by 2015, we occasionally returned to this topic due to public interest, and it was always great to come back to it since we could never exhaust all the possibilities our research data offered us because we quickly got busy with other things.

The journalists at Bayern 2 probably learned about our research through an article I wrote for Die Literarische Welt two years ago:

This article draws on the main results of our study originally presented at the DHd2015 (in Graz) and DH2015 (in Sydney) conferences.

An interesting by-product of our work was the “TIWOLI” app (“Today in World Literature”) with iOS and Android versions (which we introduced in this blog in 2016). And, of course, there’s the TIWOLI Twitter bot, run by our colleagues at University of Cologne.

In 2017, we finally managed to release the corpus on which our research is based, the “Corpus of German-Language Fiction (txt)” (doi:10.6084/m9.figshare.4524680). The corpus contains 2,735 German-language prose works (mainly novels and short stories) by 549 authors, ranging from about 1510 to the 1940s (the bulk of the texts dates from 1840–1930). [On a sidenote, our corpus was also used by Severin Simmler to fine-tune a German BERT model to adapt it to the literary domain.]

To extract the mentioned month names and concrete days, we used Jannik’s cutting-edge HeidelTime engine. As you can see in the flower-ringed histogram featured on the newspaper page, the month of May is by far the most frequently mentioned month in the corpus. In addition, the 1st of May is, also by far, the most frequently mentioned day of the year, with 249 mentions in the corpus.

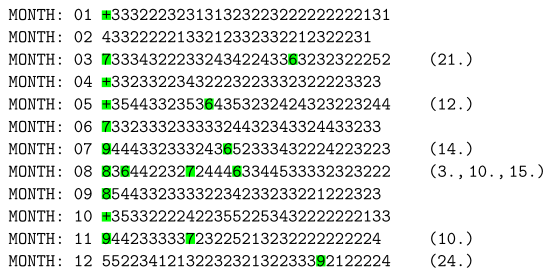

Here is an overview with the frequency of all days as we extracted them from the corpus (‘1’ means 0–9 occurrences, ‘2’ means 10–19 occurrences, etc., ‘+’ means 90 or more occurrences):

(slide taken from our DHd2015 slideset).

HeidelTime can extract various forms of dates, so here it has managed to extract “1. Mai”, “1. May” as well as “erste” / “ersten Mai”. Some example sentences:

- “Ich telephonierte Montag nachmittag (also am 1. Mai) dem Witschi nach Gerzenstein, er möge mich in meinem Bureau aufsuchen.” (Glauser: Wachtmeister Studer)

- “[…]; den 1. May 1772 reiseten wir aus Gondar ab.” (Knigge: Benjamin Noldmanns Geschichte der Aufklärung in Abyssinien)

- “Du sollst doch auch wissen, daß heute der erste Mai ist, du Einsiedler!” (Dahn: Ernst und Frank)

- “Am ersten Mai anno domini 1835 war zu Haimbach ein großes Frühstück.” (Stifter: Feldblumen)

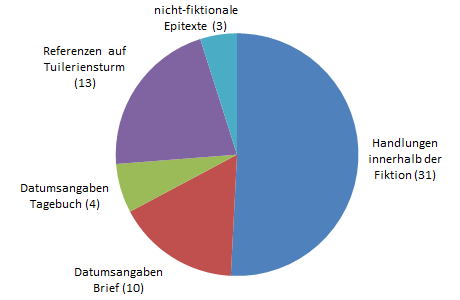

Now we’ve always wanted to dig a little deeper into our dataset to go beyond mere quantification, and we’ve demonstrated this idea by qualifying all mentions of the 10th of August:

(slide with German labelling taken from our DHd2015 slideset).

About three quarters of the mentions were plot-related (i.e., something happened on a 10th of August, including date references in epistolary novels and fictitious diary entries). But more than 20% were non-plot-related date mentions, instead a reference to the 10th of August 1792, a decisive event of the French Revolution, when armed revolutionaries stormed the Tuileries Palace in Paris. This date is a constant reference point in our corpus of German fiction and makes for a high number of non-plot-related date mentions.

For our focal date, the 1st of May, this problem is even more complex. Many feasts and customs are associated with this date, such as Walpurgis Night and the Maypole Dance, and since 1889 also International Workers’ Day. All these meanings can overlap when a 1st of May is mentioned and it is very difficult to decide whether a mention of the day refers to a plot-related event or not.

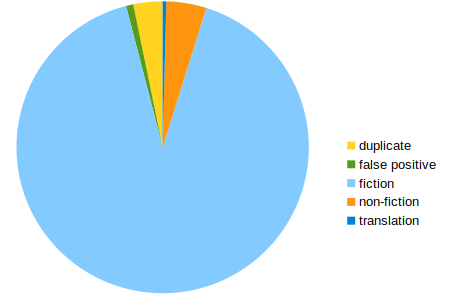

To start somewhere, however, let us first measure the precision of the 249 mentions counted and say something about the reliability of the data we generated and evaluated at the time. There are only 2 false positives, the rest is a problem of corpus composition. It is meant to be a corpus with works of fiction (hence the name), but some non-fiction works have slipped in (as already detailed in the corpus description on Figshare). Some mentions are duplicates, and one work (by Strindberg) made it into the corpus of German originals, although it is a translation). Here’s an overview:

correctly extracted from fiction: 226 – from non-fiction: 11 –

duplicates: 8 – false positive: 2 – from translations: 1.

Although we cannot say anything about recall in our exploratory study, the precision of HeidelTime is really good. We knew that before, of course, but never really detailed this. So this blogpost confirms the special role that May plays in German prose literature, even if the means we used at the time are far from being able to provide an exhaustive answer to the questions of “when literature takes place”. But it was a start.

You can explore our findings yourself in an enhanced subset of our data, which we never formally published before. So here is a list of 1st of Mays mentioned in German fiction (in the ‘timex value’ column, HeidelTime automatically tried to assign years from the surrounding context of a mentioned date, which was not always successful, but we left this column in, even though we never used this data). The file format is CSV: