1. Introduction

1.1. TL;DR

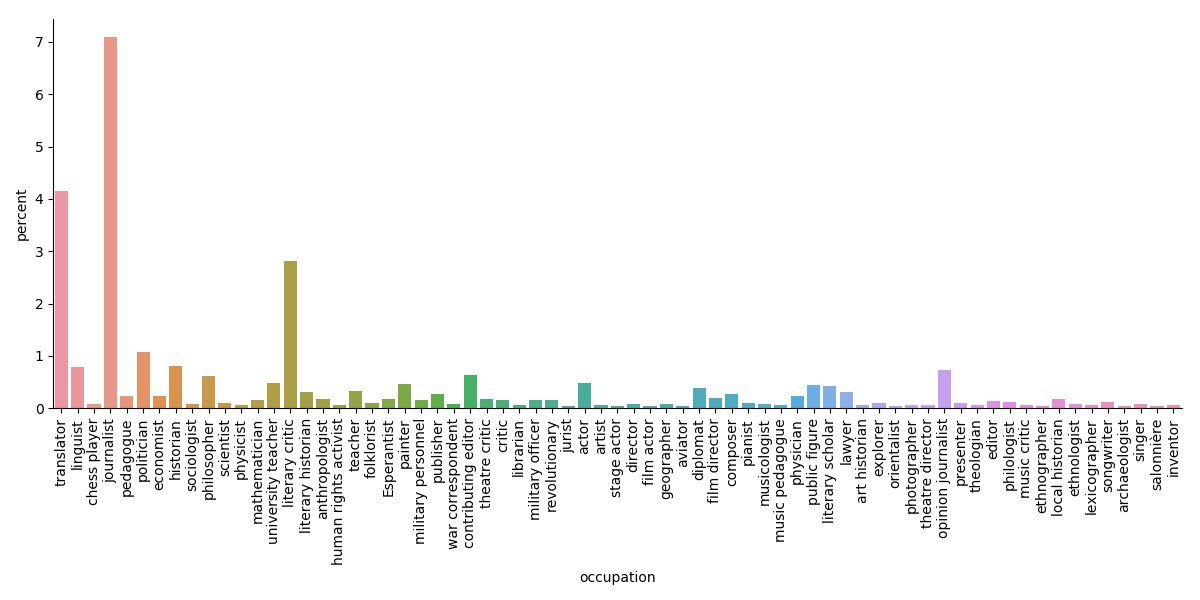

This is a little experiment which we conducted in a limited amount of time (one week). We wanted to find out how the range of jobs practised by Russian writers throughout history is represented in Wikidata. Since Wikidata is primarily filled in an automated fashion, we wanted to look for systematic errors in that process. However, we also dared to interpret the data on Russian authors at least a little, even if at this point it is neither complete nor specifically curated within Wikidata. As an appetiser, have a look at fig. 3:

No surprise there, writers generally tended to (also) be journalists, translators, literary critics. But now onto some details of our exercise…

1.2. “Underwater Basket Weaving”

Originally, according to Wikipedia, “underwater basket weaving” is an idiom “referring in a negative way to supposedly useless or absurd college or university courses”, or it can serve as an “intentionally humorous generic answer to questions about an academic degree”. As we were working on our project, we encountered a writer whose occupation was marked as “basket weaving”. In search for a good Russian translation we’ve encountered the idiom mentioned above. It seemed so funny and to the point that we named our project after it. During Soviet times, many famous writers were not officially recognised as such. Hence, they had to do some pseudo or meaningless work, something along the lines of “underwater basket weaving”.

1.3. Russian Writers’ Professions and Languages

The original goal of our project was to check the variety of jobs held by Russian writers. This is of interest since for the most part of Russian history it was hard to make a living off of just being a writer. Next to that question, and since we were experimenting with Wikidata, we also thought it would be interesting to see what languages except Russian the writers were able to speak. This could be interesting as an indicator of (foreign) cultural influences on Russian literary history.

1.4. Using Wikidata to Answer Scientific Questions

Using Wikidata as data source is fun, but problematic. In order to draw conclusions from analysing this data, you have to understand how data enters Wikidata and how it is maintained. Although human users can still alter single facts just like on any other project of the Wikimedia family, the interesting part of the Wikidata experience is that most of the processes are automated. So instead of correcting single facts, it is far more interesting to look for systematic errors.

While there are heavily curated subsets within Wikidata (like the one on Holocaust-era ghettos), our chosen subset of Russian writers is what it is at the moment and hasn’t seen any concerted action regarding its curation (at least not yet). However, we did dare to interpret the data on Russian authors at least a little, even if they are at this point neither complete nor specifically curated in Wikidata.

1.5. Ways to Automatically Improve Wikidata Using Bots

After collecting systematic errors, we also looked into ways to automatise the process using bots. Since we didn’t have a lot of time, we didn’t succeed to actually apply a bot, but we experimented a little and plan to explore this further, maybe in shape of another course work in the coming semester.

2. Description of Data Source

2.1. Wikidata

Wikidata is a free and open knowledge base that can be read and edited by both humans and machines. Wikidata acts as central storage point for structured data of all projects of the Wikimedia family (but is not limited to that). Each entity in Wikidata has a label (a name, for example), an identifier and several statements (such as “occupation”, “day of birth”, etc. for people).

2.2. Russian Wikipedia for Fact-Checking

When we spotted something suspicious in Wikidata, we cross-checked this information with the Russian Wikipedia. There were a lot of misattributions and systematic mistranslations, so we checked the original articles in Russian to find the source for this kind of mistakes.

2.3. Pywikibot Library

As Wikidata provides the instruments for automated editing, we set out to fix some Wikidata mistakes using a bot. There is a special Python library for that, Pywikibot, which can be used to create a bot. It can be launched in different ways among which we chose to host it on the Wikimedia labs environment using PAWS: A Web Shell.

3. Workflow

3.1. Querying Wikidata

We used Wikidata to identify Russian writers and their respective occupations, languages spoken, gender and year of death. To be able to look into temporal distribution, we chose the year of death as marker because we thought this was closer to their active time as writers than their birth date. The obvious limitation that comes with this approach is that writers still alive or ones lacking a year of death were not included into the analysis. But this way we were also closer to the canon of Russian literature, making us a bit more independent of Wikipedia’s “contemporary bias”.

3.2. Dataset Creation

Now, how did we find our set of Russian writers? We included people labeled as writers in Wikidata. They had to be either Russian by their nationality, have Russian as a native language or have to lived in the Russian Empire, the USSR or the Russian Federation. We excluded all people who did not feature Russian among their languages.

3.3. Systematic Problems in Wikidata

As we reviewed our raw data, we noticed a couple of errors and tried to classify them. We also made a table of all the mistakes we’ve encountered in order to then check whether they could be fixed by a bot (a link to our GitHub is below).

3.4. Attempt to Create a Wikibot

As Wikidata is an open resource with an enormous amount of data, using bots is actually dangerous. So, there are some mandatory stages you have to go through when creating a bot. We set up a regular Wikimedia account. To clarify that it is a bot you just have to mention the word “bot” at the end of username. To be approved to work on Wikidata your bot has to make several operations which will be assessed. If everything is good, the bot gets approved. When writing your bot script you can test it on the Wikidata:Sandbox.

Ultimately, we did not get to the stage of approval this time around because of struggling with several problems in the preparation process. Details are described below.

3.5. Manual Corrections

Due to the limited amount of time, we did not get to the point were we could correct systematic errors. Since our dataset is very limited, we manually corrected all mistakes spotted, and then repeated our queries.

3.6. JSON Unification in Python

Our queries initially had every writer occur as many times as he had professions plus spoken languages. To make the JSON more convenient, we wrote a Python script to transform raw data into a dictionary with unique names under which was stored a multi-layered dictionary of occupations, known languages, gender and year of death.

3.7. Visualisation in Python

The created dictionary was used to visualise information with by help of the following Python libraries: pandas, seaborn and matplotlib. At first, the data was reorganised into tables in order to create pandas dataframes. Thereafter, the seaborn graphs were compiled based on the aforementioned dataframes. Visual aspects were set up such as labels of the axes, captions, colour palettes, fonts, etc. Finally, all the charts were saved and displayed via matplotlib library.

4. Wikidata Errors

4.1. Mistranslations

Most of the problems we faced in our research were systematic, for example, mistranslations. It is quite obvious that Yanka Kupala was not an “imagemaker”. The error occurred due to automatic translation. In the Russian WP he was marked as “публицист” (transcribed “publicist” = “opinion journalist”), but the automatic translated the publicist back to “имиджмейкер” (“imagemaker”).

4.2. Misclassification Due to Mistranslation

In many cases there was a generic name instead of the actual job title (mostly due to mistranslation). For example, according to Wikidata, Bulgakov is speculative fiction and Gennady Malakhov is urine therapy. Such mistakes can be found easily, though. If as an occupation there is an entity which is not an ‘instance of profession’ but rather ‘instance of genre’ or something similar, it is an error. Yet in some cases there is no easy way to derive the original mistranslated job title as sometimes the mistranslation is too vague, such as ‘Orthodox Christianity’, making it harder to find out what the original job title was.

4.3. Redundancies

The last systematic problem we came across was the replication or synonymous labelling of entities such as “police officer” (Q361593 and Q384593) or ethnologist (Q1371378) versus ethnographer (Q12347522). Yet sometimes it is not quite clear whether articles should be merged. It is not obvious whether “official” (“должностное лицо”, Q599151), “official” (“чиновник”, Q382887) and “civil servant” (“государственный служащий”, Q212238) convey the same meaning.

4.4. Wikibot for Error Correction

Bots can be useful in solving some of the problems described above, especially in cases of misclassification. This involves the automated changing of statements, which is more complicated than just changing labels like for mistranslations.

However, the main problem we encountered was connected to bot testing within the sandbox. The structure of the sandbox is very different from the actual one, the two do not contain any identical entities, meaning there are no pages of Russian writers in the sandbox equal to the ones in the original Wikidata. In order to test our bot we had to create like 10 to 20 pages, imitating the actual Wikidata pages with all the properties we need, and only then try to work with our bot on this material. In the short amount of time that we had to prepare our project, we did not succeed to do so, but this is where we would have to continue next time around.

5. Results and Tentative Interpretations

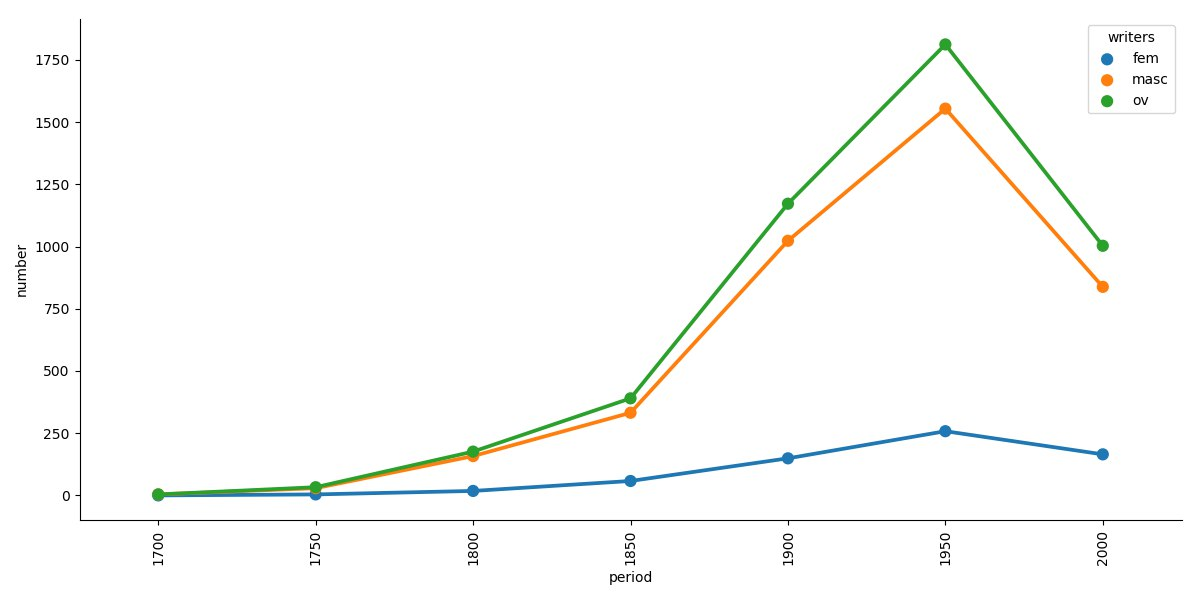

We identified 8160 Russian writers in Wikidata meeting our eligibility criteria. Not all the fields were filled in for all of them, so those who lacked some pieces of information were excluded from the corresponding analysis. For example, we couldn’t put writers without year of death in our timeline. The amount of data on those who already have attributed a year of death can be seen in figure 1. As expected, the period best covered is the 20th century. The amount of data for the 19th century was significantly lower, and the first half of the 21st century appears to be under-represented, too, for obvious reasons.

5.1. Occupations

5.1.1. General

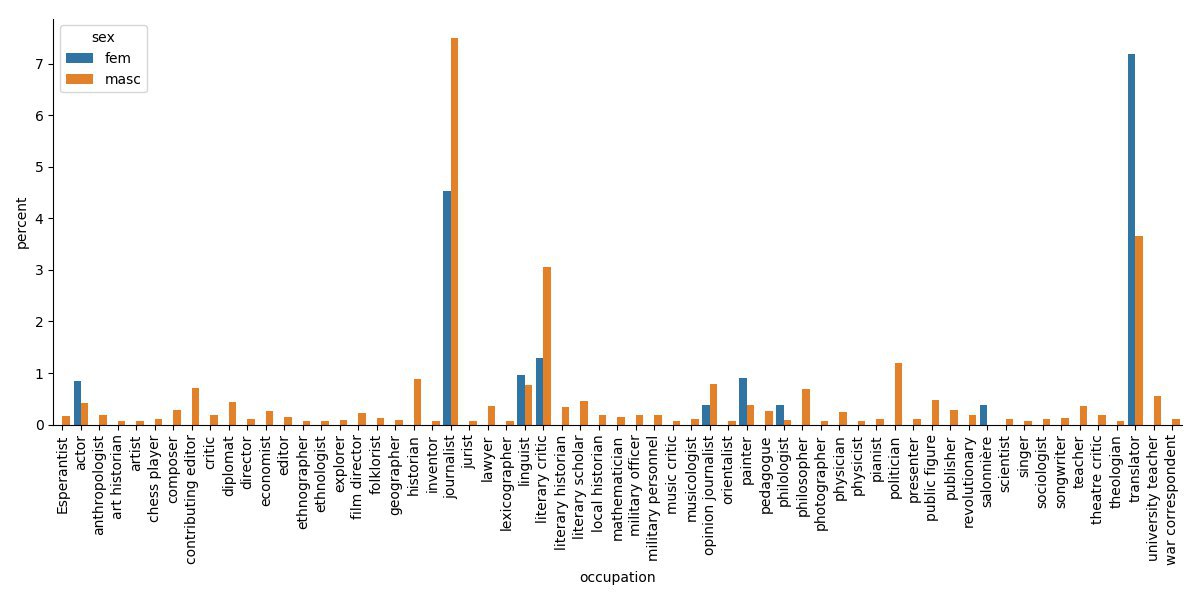

Figure 2 shows the distribution of different occupations of Russian writers. Unsurprisingly, the most popular professions are those where the ability to write well is a prerequisite: journalism, translation, literary criticism.

5.1.2. By Time

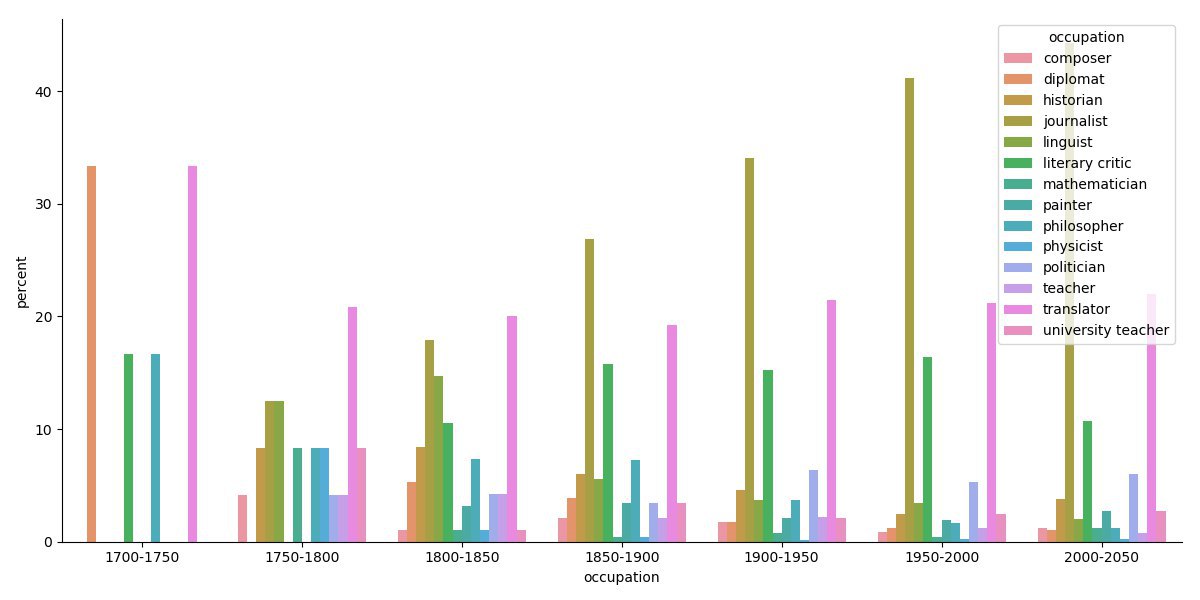

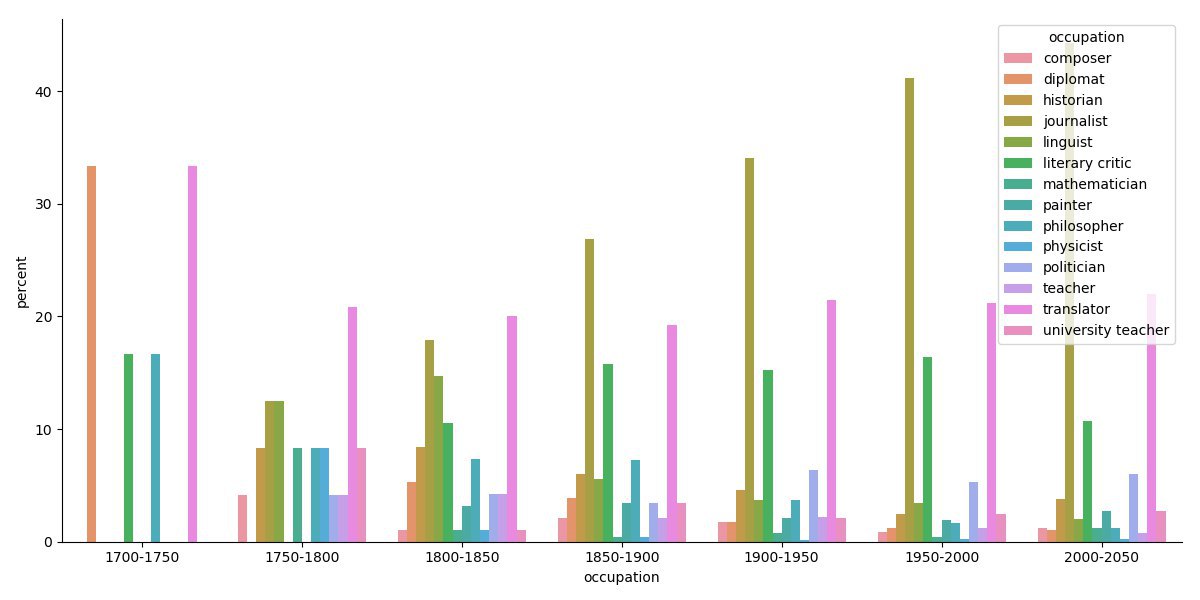

Figure 3 only shows the professions that had more than 5 people assigned to them in each period. We witness the decline of linguistics, philosophy, criticism, translation, diplomacy, history, education over the centuries, possibly also due to a diversifying landscape of professions, and the rise of journalism.

5.1.3. By Gender

Figure 4 shows that women writers had fewer professional options in past centuries, mostly limited to “work from home” options. They worked as interpreters, linguists, philologists, artists or were salonnières. An exception to this rule are the actresses among women writers.

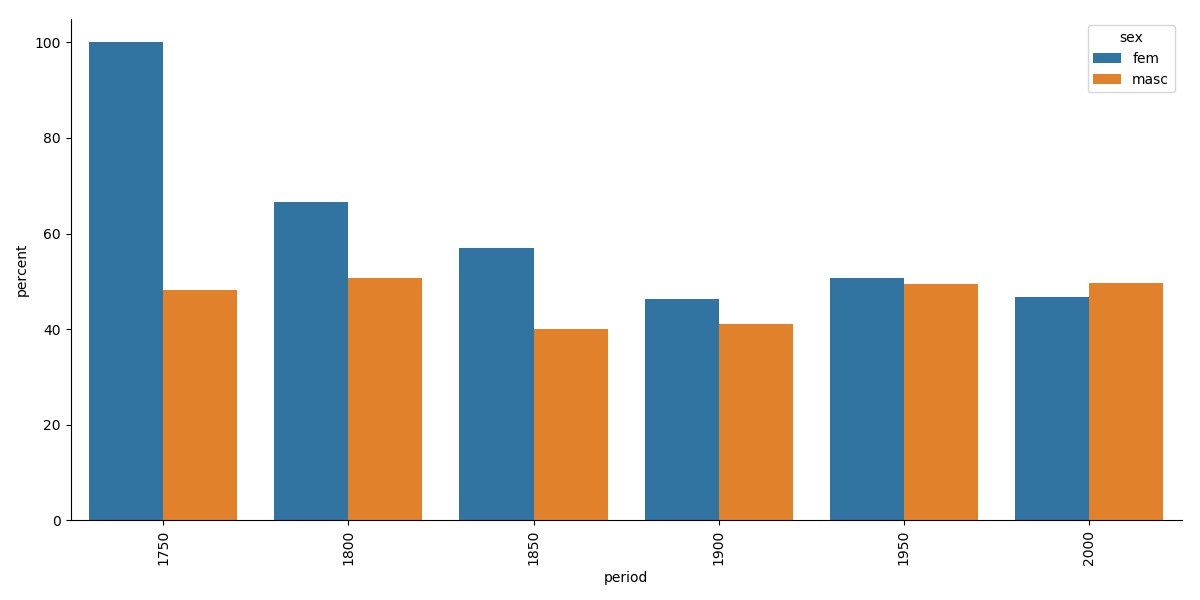

5.1.4. Just a Writer (by Time & Gender)

Figure 5 shows the percentage of writers only marked as writers on Wikidata without additional occupations. The situation remains quite stable considering men, whereas the percentage of women falls from 100% to approximately 70% by the beginning of 19th century and then gradually declines to 45–50%. We tend to explain this by the fact that women gradually entered the labour market. Towards the 21st century, there is a 50% chance that being a writer means that a person also has an additional profession, according to Wikidata.

5.2. Languages Spoken

5.2.1. General

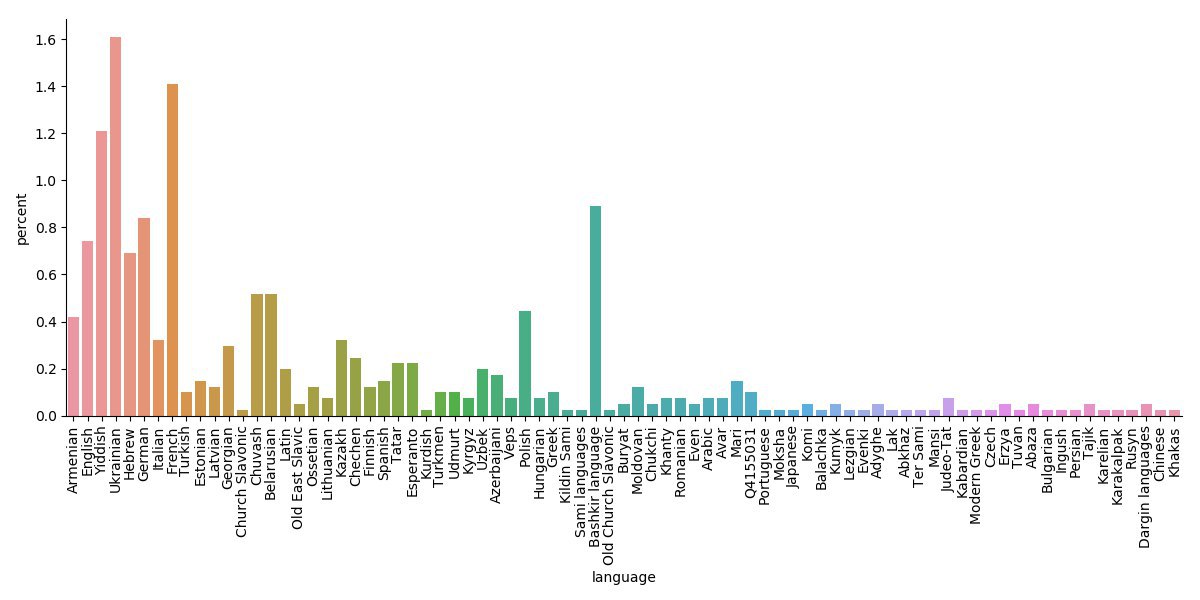

Figure 6 shows the distribution of additional languages Russian writers spoke or wrote in. There are two distinct types of languages: native regional languages spoken in territories of the former Russian Empire and the USSR (Ukrainian, Bashkir, Yiddish, etc.) and secondary European languages (French, German, English, etc.).

5.2.2. By Gender

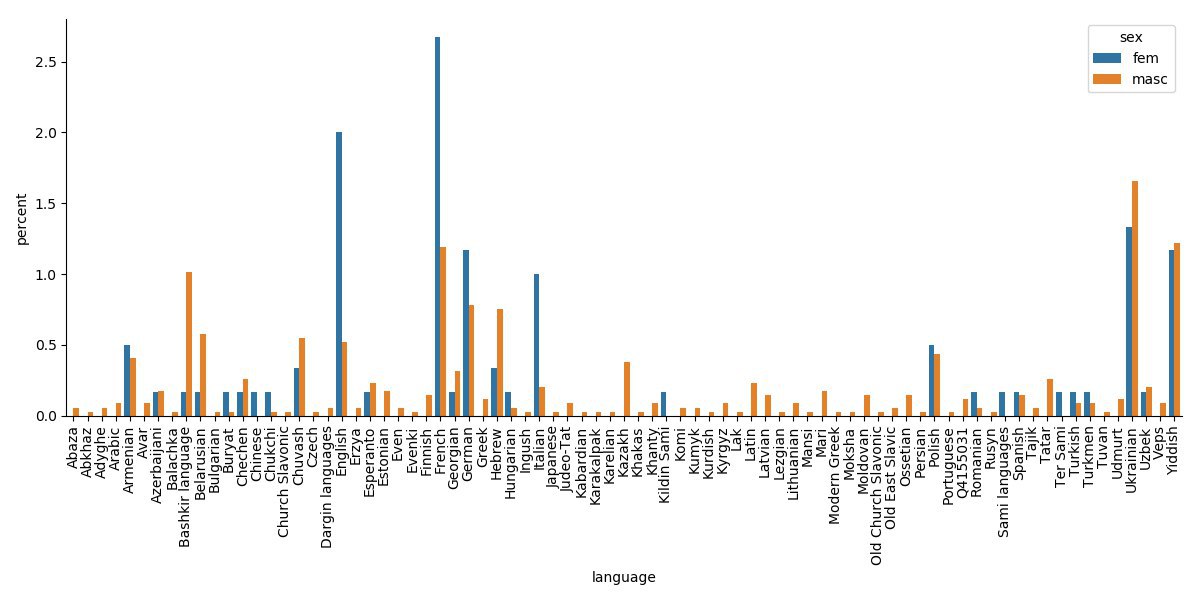

Figure 7 uncovers some interesting tendencies. Women writers in our data set mastered more European languages, such as English, French, German, and Italian, than male writers did. Women also knew better than men some smaller, less well-represented languages, like Armyan, Buryat, Hungarian, Saami.

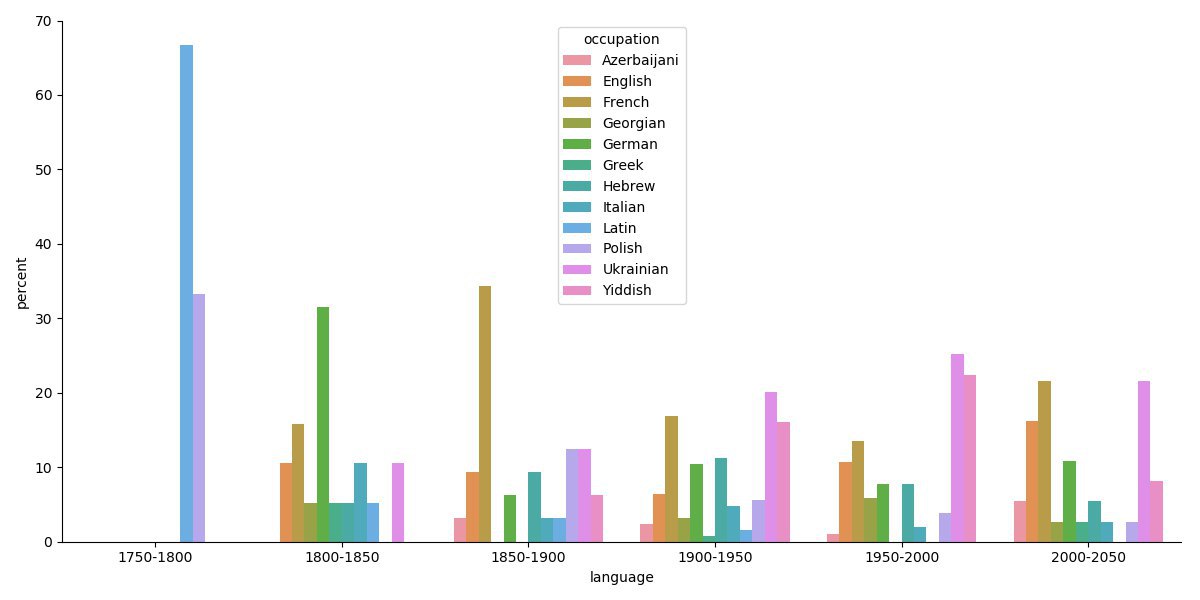

5.2.3. By Time

The distribution of languages spoken by Russian writers by time (figure 8) can reflect cultural influences of given periods. Between 1800–1850, the most popular language was German, which might be due to the German-orientated culture established by Peter the Great. During the second half of the 19th century (1850–1900), the most popular language was French, which corresponds to the big influence that French culture had on Russian culture at the time. At the beginning of the 20th century (1900–1950), the most popular languages were Ukrainian, French and Yiddish. During the second half of the 20th century (1950–2000), English joined the parade. In the most contemporary period, the most popular additional languages are French, Ukrainian and English. It is worth noting that the gap between popular and unpopular languages decreased over time, possibly an effect of globalisation, leading to a mix of contemporary cultures and languages exerting an influence on Russian literary life.

6. Appendix

All files, Python code, images, Wikidata search queries, etc. can be found on our GitHub.