This could become a whole new series: Fancy by-products of Digital Humanities research projects…

Short version: Download TIWOLI for Android here. Download TIWOLI for iOS here.

Update (Oct 29, 2016): The iOS version is finally available in the App Store. The article was updated accordingly.

And now let’s jump right into it and name seven famous days in world literature:

That is an easy start, but the world beyond this über-day of world literature is trickier. Most people will know about the fictional events we’re going to itemise, but won’t typically have the exact dates in mind. Let’s check:

- On which day did Robinson Crusoe set foot on his island? (September 30) On which day did he eventually return to England, after 35 years of absence? (June 11)

- When is the deadline for Phileas Fogg’s travel around the world in eighty days? (December 21)

- What’s Tristram Shandy’s birthday? (November 5) – Funny enough, there still seem to be people drinking to Tristram Shandy’s health.

- When did Goethe’s “Young Werther” commit suicide? (December 21)

- On what day did Charlie visit the Chocolate Factory? (February 1) – Especially interesting to note here that in the 1971 movie, the golden ticket refers to “the first day of October” for whatever reason.

So this is the subject of our blogpost, (in)famous days in world-literary fiction.

How did this come about? At the annual ADHO Digital Humanities conference 2015 (DH2015) in Sydney, we delivered a talk called “When does (German) literature take place?” (slides) In order to answer that unusual question, we extracted exact dates and months from a corpus of 2,700+ works of German-language fiction from 1510 to the 1940s. Our results suggested that “the marvellous month of May” (Heinrich Heine) is preeminent in our corpus of German fiction. There was already enough evidence to claim that May is the favourite month of poets (at least in the northern hemisphere), and Heine is just one example. But May’s preeminence in prose was a real finding and there are a bunch of explanations, but this (along with many other insights yielded by this whole date-extraction-from-fiction business) shall happen in the corresponding research paper, not here.

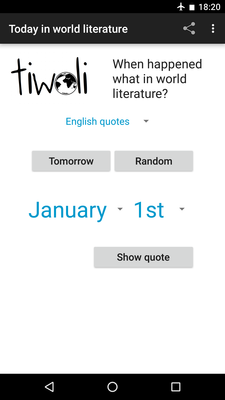

As a by-product (and no more than that), we coded a native Android app to showcase the more exciting and self-explanatory of our results. We called our app TIWOLI (short for “Today in World Literature”) and made it available via the Google Play Store. This was followed by the iOS version, done by our dear friend Thomas Bögel.

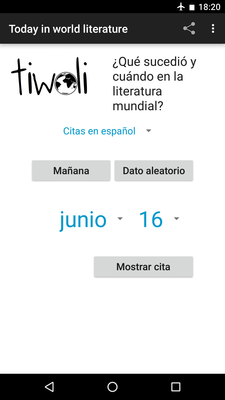

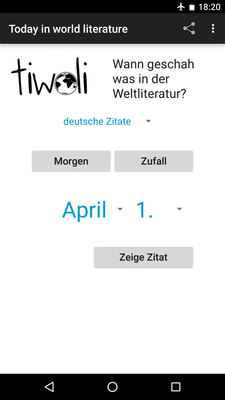

Now what TIWOLI does is give you the opportunity to zigzag through an entire world-literary year, a calendar filled with fictional happenings. Here some screenshots with some of the examples from above:

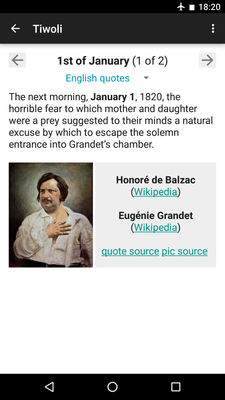

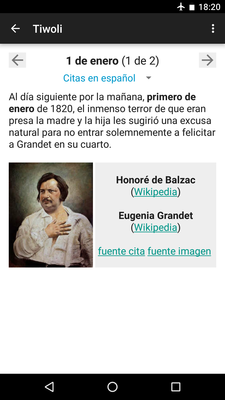

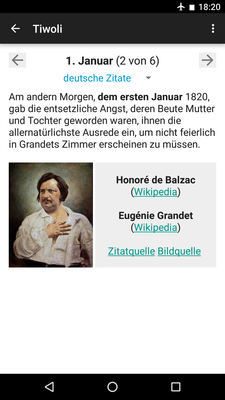

We’re currently curating three corpora for the app, in English, Spanish and German. In some cases, you can even switch between translations of one and the same passage (not in all cases, though, the contents of our corpora are very different per language). This is a 1st-of-January example from Balzac’s novel “Eugénie Grandet”:

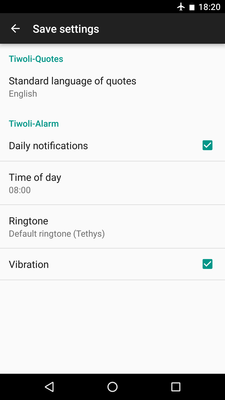

The interface was also translated into the three languages (it will fall back to English if your system language cannot be matched). Here are the three versions of our welcome screen, plus the English version of the settings page:

If you like you can set the alarm so it informs you about fictional events that “happened” on the current day.

It was not all that easy to fill up a whole year with suitable quotes for every day. To replenish the English corpus with nice enough quotes we are very grateful to Mark Algee-Hewitt and the Stanford Literary Lab who helped us out with their corpus of English-language fiction. Let’s give you some more:

For each corpus, the app contains quotes from translated world-literary works, too, because after all, weltliteratur is the raison d’être of this blog:

The dates from the Russian 19th-century novels point to the Julian calendar, of course (which was 12 days behind the Gregorian back then). Some more translated literature:

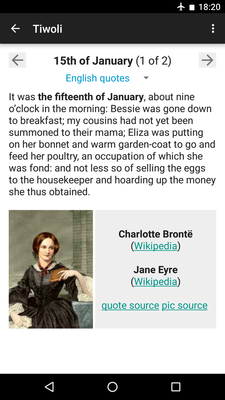

For every quote we provide a link to the full-text source (gutenberg.org, gutenberg.net.au, archive.org, books.google.com, …). Epitexts and links/metadata are generated automatically. The portraits/pictures were not chosen by us, we’re relying on the ‘principal image’ provided by Wikidata, a great way to easily enrich an app. Let’s give you the Defoe examples from above, accompanied by Poe (for the sake of rhyming names):

Some more German literature in translation, including the aforementioned destiny of storm-and-stressy Werther:

The first two quotes are from Fontane’s “Effi Briest”, in many respects the righteous German counterpart to “Madame Bovary”. The second quote alludes to Effi’s and Instetten’s wedding which coincides with the national day of Germany (not a good omen, given the tragic outcome of the novel 😇).

Four final examples from the English corpus:

The last quote, from “Jekyll & Hyde”, is interesting insofar as the given date can be regarded a mistake by the author that went into several print editions (as discussed here, for example).

We also harvested some newer books as you can see in the Auster example below (the picture is not the best, but somebody might upload a better one to Wikimedia Commons someday). There’s also one more Brontë quote and two nice quotes from the time-travel novel by Bellamy (where times and dates are the actual subject):

Now let’s sneak a peek at the Spanish corpus. You can easily switch to the other corpora at any point from within the app.

We can also follow the chronology of Borges’ cuento “La muerte y la brújula” (“Death and the Compass”):

Some concluding Spanish examples:

On to the German-language corpus:

The first quotation, from Georg Büchner’s novella fragment “Lenz”, is probably one of the most famous first sentences. On the second screenshot, Schnitzler’s “Leutnant Gustl” is pondering his destiny on 4th of April, resulting in not killing himself. On the third one, the government of the Martian States takes control over our planet, because we earthlings are not capable of maintaining peace (the author of the passage, Kurd Lasswitz, can be regarded a pioneer of German sci-fi lit). The fourth quote is especially interesting, since the “27th of July” is also discussed in a “meta” way, as a combination of a printed number and a word, which serves as intellectual nourishment for the imprisoned intellectual (if you didn’t install the app yet, check the English translation of this passage on Google Books).

We already featured Theodor Fontane with some paragraphs translated to English. But what is it with the Prussian author and the 3rd of October? It is an eventful day in many of his novels, and we’re not sure if anyone has looked into that yet:

Fitfully, we included some quotations from contemporary fiction. The given sources contain page numbers as they point to print editions of the works:

Some more:

The first quote from Arno Schmidt’s 1972 novel “The School for Atheists” points to a future date, the 7th of October, 2014. When we traversed this point in time two years ago, at least one major newspaper published an article about this long-imminent event (German weekly “Die Zeit”: “The story starts now.”).

How about Jean Paul, the greatest of all May lovers:

And last not least, some Christmas quotes:

So much for our app, TIWOLI. Also if it wasn’t part of the original research, it helped to sharpen our notion of dates and month names in fictional texts. Literature as a genre has an inclination to waive exact dates and prefers temporal settings like “at the beginning of November”, “It was a dark and stormy night”, etc. But sometimes exact dates do occur, of course. And if they do, they have a tendency to mean something. (Unless, of course, they occur in epistolary, adventure or historical novels which are usually full of exact dates. We tried to exclude them from the app and just used some as fill-ins. Goethe’s “Werther”, all Jules Verne novels and Benito Pérez Galdós proved especially useful. 😊)

Before we conclude this admittedly BuzzFeed-like über-post with far too many pics we have two cliffhangers for you:

- Our friends at the University of Cologne (Spinfo/CCeH) are currently building a web interface with our data. Prototype looks very promising.

- There’s an easter egg somewhere in the app. Whoever finds it first is our hero/ine!