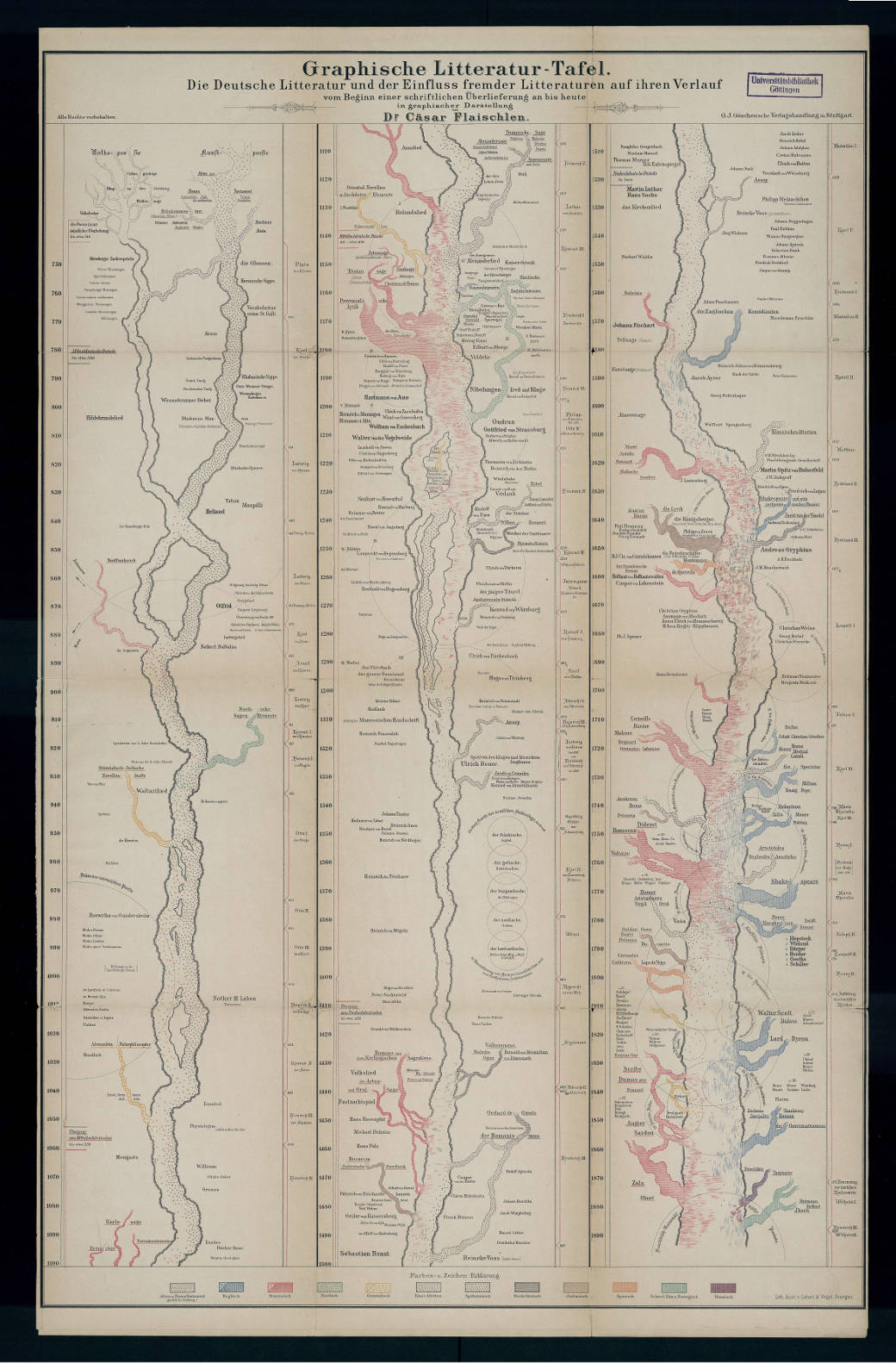

Exploring the influence that authors have (or might have) exerted on other authors is among the standard procedures pursued by scholars of (Comparative) Literary Studies. Provided the right type of data, these kinds of relations can be easily visualised in a network graph with arrows pointing in myriad directions: X influenced Y and, possibly, vice versa. What we have here, though, is a collection of unidirectional pointers which – in the form of streams of movements, events, works, and authors of world literature – exert their influence on one particular, ever-broader river: German literature, its manifold protagonists and epochs.

It is Cäsar Flaischlen’s “Graphische Litteratur-Tafel” (Graphic Literature Table) we’re talking about, a 58×86.5-cm poster published in 1890, and a flamboyantly beautiful one:

We came across this table just a couple of weeks ago, and quickly purchased a copy via ZVAB.com, scanned it, OCRed the 8-column preface, encoded both the text and the graphic table in TEI and put up a website to present the data, at litteratur-tafel.weltliteratur.net (still in alpha!). Simultaneously, we had another copy scanned by the Digitisation Centre of Göttingen’s University and State Library; you can download their hi-res version here (PDF format, 4.5 MB).

The Author

How did this chart come about? Cäsar Flaischlen (1864–1920) was not much of a practising literary scholar, nor an academic. The dissertation he wrote (on the Enlightenment playwright Otto von Gemmingen, with a nod to Diderot) was not well-received by his colleagues (one of which said it was “ziemlich nachlässig und schleuderhaft”, i.e., “quite sloppy and negligent”). Flaischlen’s dissertation was published in 1890, the same year in which his “Graphic Table of Literature” saw the light of day. Then he left academia to continue writing (dialect) poetry, novels and plays, while working as an editor for arts and literary magazines to pay the bills. (There’s an article on him in “Deutsches Literatur-Lexikon. Das 20. Jahrhundert”, vol. 9, 2006.)

Context I: Positivism

Flaischlen does not mention any of the sources from which he compiled his graphic table. The canon of authors and other entities he mentions is not in the least controversial and was part of the literary-historical consensus taught at universities at the time. Flaischlen’s impressive visualisation calls upon the power (and shortcomings, too) of positivist thinking (there are remarks on the outdatedness of Flaischlen’s approach in this 2012 introduction to Comparative Literature).

Positivism is largely seen in a negative light today, but one of the aspects behind it has been vividly discussed recently in the attempt to reinvent the Humanities along the lines of the natural sciences. “The natural sciences ride triumphantly in the chariot of victory to which we are all chained”, wrote Wilhelm Scherer, a central representative of positivism in the 1870s and 1880s. Trying to establish Literary Studies as an “exact science” was by no means unusual, as we can see in another quote by Shakespeare scholar Wilhelm Wetz who, in the 1890s, wanted to prove that Literary Studies, too, “can rise to the ranks of the exact sciences” (p. VII).

At the same time, Flaischlen’s flowchart stands in opposition to a popular positivist undercurrent of his time, biographism. Instead of looking painstakingly for possibly undiscovered details in an author’s life according to the biographistic paradigm, he dabbles in a kind of macroanalysis, an abstract model of the big picture, the organic connection.

Another aspect of Flaischlen’s chart is how he deals with the question of crafting a history of literature. The first half of the 19th century had a more philosophical approach. Literary history was understood as self-realisation of a mind, of an idea. This changed in the second half of the century. Erich Schmidt (who had studied under Scherer) described the new paradigm like this (in his inaugural address at the University of Vienna in 1880):

“Litteraturgeschichte soll ein Stück Entwicklungsgeschichte des geistigen Lebens eines Volkes mit vergleichenden Ausblicken auf die anderen Nationallitteraturen sein. Sie erkennt das Sein aus dem Werden und untersucht wie die neuere Naturwissenschaft Vererbung und Anpassung und wieder Vererbung und so fort in fester Kette.” (p. 491)

This approach seeks to understand a national literature in its interconnectedness to the literature of other countries. In the same article, Schmidt continues:

“Wie steht man zum Ausland? Der Begriff der Nationallitteratur duldet gleichwohl keinen engherzigen Schutzzoll; im geistigen Leben sind wir freihändlerisch. Aber ist Selbständigkeit oder Unselbständigkeit, größere Receptivität oder Productivität, wahre oder falsche Aneignung sichtbar, und wie hat die deutsche Litteratur sich allmählich zu universalistischer Antheilnahme emporgearbeitet?” (p. 493)

By and large, that is the point of Flaischlen’s flowchart.

At the time, one of the leading ideas about the history of literature was Scherer’s “Wellentheorie” (wave theory). This theory assumes that literature blooms and decays periodically, thus adopting the metaphorical form of a wave (or waves), peaking roughly every 600 years. Supposedly, the last heyday of German literature happened at around 1800. So according to the theory, contemporary literature (i.e., around 1890) would find itself in a period of decay, something that will not have found Flaischlen’s approval. He was an adherent to the naturalist movement of his time and a poet and novelist himself. His river model of German literature can thus be seen as a polemical remark about Scherer’s theory. Although the river narrows after 1200 (maintaining accordance with Scherer’s view), it becomes ever broader even after 1800, foreign influences stream into it, and the watery body of Germanophone literature absorbs, accumulates, amalgamates everything.

Context II: Visualising Time

Flaischlen was not the first to come up with the idea of representing a timeline as a river. This visualisation metaphor goes back to Austrian historiographer Friedrich Strass (1766–1845) who in 1804 published his highly influential “Strom der Zeiten” (“Stream of Time”). A hi-res scan of this chart was made by the Munich Digitisation Center (MDZ).

Rosenberg and Grafton discuss “Der Strom der Zeiten” in their fabulous compendium “Cartographies of Time” (2010, pp. 143–149). And they quote William Bell, the English translator of Strass’s impressive chart, who (in 1810) emphasises the qualities of the river metaphor:

“However natural it may be to assist the perceptive faculty, in its assumption of abstract time, by the idea of a line, (…) it is astonishing that (…) the image of a Stream should not have presented itself to any one (…). The expressions of gliding, and rolling on; or of the rapid current, applied to time, are equally familiar to us with those of long and short. Neither does it require any great discernment to trace (…) in the rise and fall of empire, an allusion to the source of a river, and to the increasing rapidity of its currents, in proportion with the declivity of their channels towards the engulfing ocean. Nay, this metaphor (…) gives greater liveliness to the ideas, and impresses events more forcibly upon the mind, than the stiff regularity of the straight line. Its diversified power, likewise, of separating the various currents into subordinate branches, or of uniting them into one vast ocean of power (…) tends to render the idea by its beauty more attractive, by its simplicity more perspicuous, and by its resemblance more consistent.” (pp. 143, 147; original quote here)

As a positivist approach, Flaischlen’s flowchart is non-controversial. The only thing that could appear controversial is the impact (breadth) of each of the influxes. He himself stresses in the last paragraph of his preface “that the breadth of the main river is not mathematically calculated”. His chart is not based on “data”; it is not yet part of those 19th-century movements that started to use numerical statistics to transform “knowledge” into “data knowledge” (“Datenwissen”, cf. Andreas Bernard: Das totale Archiv, Merkur, 2016). But his “Graphische Litteratur-Tafel” is an inspiring predecessor of our attempts today to use “graphs, maps, trees” to visualise and explore literary data.

Bibliography

Bernard, Andreas: Das totale Archiv. Zur Funktion des Nicht-Wissens in der digitalen Kultur. Merkur, vol. 801 (February, 2016), pp. 5–17. (merkur-zeitschrift.de)

Flaischlen, Cäsar: Graphische Litteratur-Tafel. Die deutsche Litteratur und der Einfluß fremder Litteraturen auf ihren Verlauf von Beginn einer schriftlichen Überlieferung an bis heute in graphischer Darstellung. Stuttgart, Göschen, 1890. (2. Tausend: Stuttgart, Göschen, 1890; 3. Tausend: Berlin, Behr, 1890)

Minor, Jakob: [Review of Flaischlen’s Dissertation on Otto von Gemmingen.] Anzeiger für deutsches Alterthum und deutsche Litteratur, XVII, 2 (April 1891), pp. 147–149. (digizeitschriften.de)

Nebrig, Alexander: Vergleichen als Wissenschaft: Zur Fachgeschichte. Evi Zemanek, Alexander Nebrig (eds.): Komparatistik. Berlin, Akademie Verlag, 2012, pp. 35–36. (books.google.com)

Rosenberg, Daniel; Grafton, Anthony: Cartographies of Time. Princeton Architectural Press, New York, 2010, pp. 143–149.

Schmidt, Erich: Wege und Ziele der deutschen Literaturgeschichte. Eine Antrittsvorlesung. Charakteristiken. Vol. I. Berlin, Weidmann, 1886, pp. 480–498. (archive.org)

Weschenfelder, Anke: Flaischlen, Cäsar (Otto Hugo). Deutsches Literatur-Lexikon. Das 20. Jahrhundert. Vol. 9. Zurich/Munich, K.G. Saur, 2006, cols. 33–37. (books.google.com)

Wetz, Wilhelm: Shakespeare vom Standpunkte der vergleichenden Litteraturgeschichte. Vol. I: Die Menschen in Shakespeare Dramen. Hamburg, Haendke & Lehmkuhl, 1897. (archive.org)

Thanks a lot …

… to Kurt Ubelhoer for copyediting this post!!!1!